People who love Brompton folding bikes really love them, enough so that they’ve been described as a cult.

Jo Johnston, who lives in Berlin and works with disabled children, says that as soon as she bought one of the small-wheeled, compact commuter bicycles, she felt part of a “club.” And that was before she founded a meet-up group that takes rides around the city and its environs.

But the machines are about more than being “in the fold,” a term Brompton enthusiasts like to use. More and more of us are living in cities, and those cities’ infrastructure is groaning under the pressure. Folding bikes, say their fans and designers, can combine with mass transit to make sense of living in a metropolis.

Members of London Brompton Club at Abbey Road.Image: Paul Cook

Typical riders take a train into town from a suburb or a neighborhood on the city’s outskirts, and use a folding bike to cover the last miles to work. The bikes are built for lives lived in tiny apartments with little storage–they fold up small enough to fit under a table or on a shelf. They speak of autonomy, but instead of expressing the need for escape to open fields and mountains—as sports bikes might—they’re knit-up with city life.

Brompton is by no means the only folding bike brand. But it is the largest of any bike brand in the UK. This, plus its unusual London-based manufacture, its rise on the streets of the UK capital and now further afield, its distinctive shape, and its cultish vibe all drew me to the brand.

Keen for the publicity, Brompton lent two bikes to the Quartz London office. And now I understand more why Johnston sums up her experience riding a Brompton in one word: “Freedom!”

Fold along the line

Brompton enthusiasts love their bikes so much they hold competitions to see who can fold them fastest.

The company began its brand of bicycle origami back in the 1970s. Andrew Ritchie, an engineering grad from Cambridge, was introduced to an early folding-bike maker by his father, and thought he could improve on the existing design. Within a few years he’d arrived at a design recognizable as the one that Brompton still makes today.

The bikes come in four speeds and 12 colors and with myriad moderations, but they’re all based on the same design. They aren’t cheap. The bikes start at £785 ($1,040) but it isn’t hard to build that up to over £2,000 ($2,650) by making modifications.

The first Brompton bikes went into production in 1988, even though prospective backers didn’t initially see the potential. In the foyer of the company’s factory in Greenford, west London, there are framed rejection letters from Raleigh, a major bike manufacturer, and from Barclays refusing a small-business loan of £40,000.

Yet the factory is new. Growing demand for the bikes and a determination to keep manufacturing in the UK meant the company had to completely rethink its build process, says Will Carleysmith, Brompton’s global head of design. The change from “big bike workshop” to modern factory means the company can now make 45,000 bikes a year, generating £30 million in sales.

“We’re one company that has designed and refined a single product,” Carleysmith says. “We design every part of the product, which is unusual for the bike industry. That’s one of the secrets…the total nose-to-tail approach to the design.”

Carleysmith joined the firm straight out of university and has been working there for the last 12 years. Back when he started, folding bikes were still an oddity. But about five years ago there was an explosion in the industry. And with it came what Carleysmith calls ”a tipping point in certain markets in understanding the brand.”

It’s a lifestyle choice.Image: Samantha Skye

“When the first people set out in the 1980s on these tiny bikes they must have looked like lunatics,” he says. “You’d have had to have a pretty thick skin” to buy one.

Now it’s commonplace to see business people and trendy types scoot through London’s streets to their destination, hop off, and swiftly fold up their brightly colored bikes, in a piece of mechanical theater which, one rider told me, can draw applause.

The bikes are cute. They have an anti-vanity vibe, perhaps similar to the sentiment that’s currently making east London hipsters grow huge beards and waxed mustaches. They’re silly. They say: “I’m so comfortable with myself that I don’t mind looking a little bit quaint, a little bit daft.”

Brompton doesn’t have a big advertising budget, Carleysmith says, and relies on ”people buying the bike, loving the bike, boring their mates in the pub” with stories of its charms, he said. But the budget for the brand is cleverly spent, tapping into the quirky self-image of its riders. In city races, chaps in jackets and ties peddle furiously past famous landmarks. A Brompton rider in Lycra is a rare sight.

New markets

And then, of course, there’s Asia.

“Export is a huge story,” Carleysmith says. The UK is the company’s biggest market; South Korea is number two. Carleysmith says Brompton exports 80% of the bikes it makes, and Asia accounts for a third of its sales. The company also recently opened an office in New York.

Other makes thrive in Asia, including folding bikes from Tern and Strida in Taiwan, US-based Dahon and Bike Friday, and Mando Corporation, a huge manufacturer in South Korea.

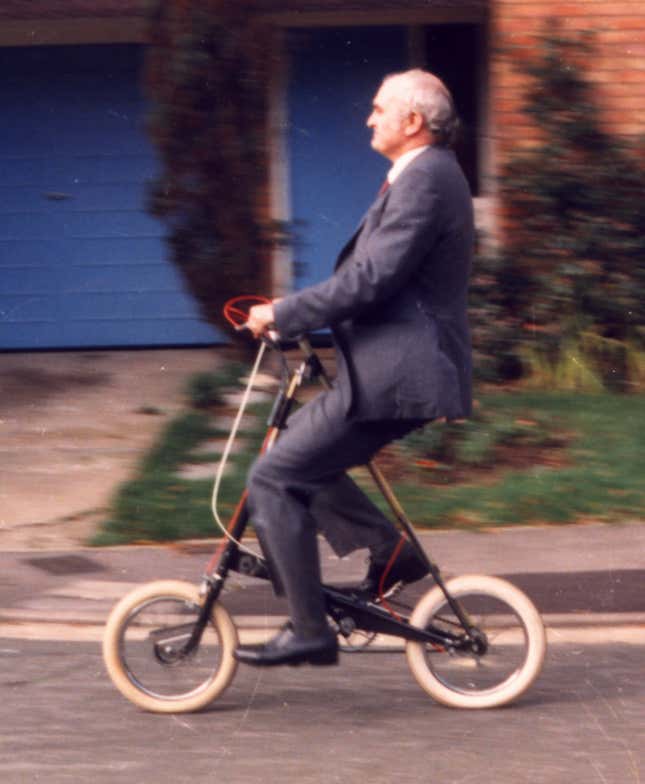

An early Strida test ride.Image: Mark Sanders

Freelance designer Mark Sanders, described to me by another designer as “the guru of folding bikes,” designed the original Strida. He’s worked on foldable technologies for years—bikes, but also kichenware, like folding chopping boards—and is delighted to see the way the funny-looking transport machines are spreading.

“There’s a bit of a stigma in the UK and America that only kids ride small-wheeled bikes, whereas in Asia, ‘mini-velo’ is kind of a cool thing,” he says. “And that’s really positive for folding bike makers like Strider and Brompton, and all the others out there.”

Nick Jones, a Brompton rider who used to run social media and the website for Number 10 Downing Street, said that a UK trade mission gave a red-and-white Brompton as a gift to the prime minister of Japan, where the bikes also “have cult status.”

Flocks and folds

It’s not just Brompton: all cycling is prone to cults. Sanders wishes it wasn’t so. He’s an evangelist for cycling’s democratic power. And he also talks about the freedom cycling offers. On a bike, he says, “you’re still on the same level as pedestrians: you can chat, and smell the coffee, smell the bakery,” he says, “and yet get places three times as fast. I mean, what’s not to like about it?”

The fold means that commuters and small-apartment dwellers also get those perks.

“Space is always a premium. And so being able to take your bike into your flat, where everything is really tiny—places like Tokyo and Hong Kong–having a bike that folds down really small is really useful.” The Brompton’s engineering makes it brilliant for that task, he says.

Sanders’ view isn’t all rose-tinted, though. “I do love Brompton. I love Andrew [Ritchie]. We get on pretty well, but we do have slightly different views,” he says.

Specifically, he sees the bike as triumphant in terms of engineering, but lacking in design. He says there are too many sharp edges.

Sanders’ Footloose for Mando design.Image: Mark Sanders

“Imagine you had such sharp corners on a mobile phone. It wouldn’t be acceptable,” he says. He wants to get his hands on the bike, to “make it more human focused, more soft and gentle.” But Brompton, he says, isn’t having any of it.

Room for growth

Another thing Sanders would like to tackle is the weather. That, and the thought of getting hot and sweaty, put too many people off cycling, he says.

Folding bikes partly solve that because you can put them on a bus or in a taxi if it starts to rain, or if you simply can’t face the exercise. But the next frontier for Brompton is incorporating electric motors to help riders up hills or on longer journeys. The company hopes to have an electric folding bike on the market in 2017.

Riding a regular Brompton took some getting used to, and I didn’t find it as comfortable as my road bike for a long commute—almost an hour each way in London traffic. So to test how the bike really interacts with cities and trains, I took it to France.

Early one London morning, I packed a backpack—the bike I borrowed didn’t come with a bag that fitted to the frame, but they’re available—cycled to the Tube, folded the bike, and took the subway to King’s Cross St Pancras. There I passed the folded bike through the X-ray machine and headed through passport control. (Two Brompton riders I met on the train said I was lucky not to have been stopped, since British security likes you to put folding bikes in bags.) Four hours and 580 miles later, I stepped out into the hot streets of Lyon. I cycled to my rented apartment, and spent the next two days exploring the city’s rivers, streets, botanical gardens, swimming pools, and surrounding countryside before heading back. It was raining in London, and I put the bike in a cab because, on a two-wheeled jaunt to Lille where we changed trains, I’d bought too much French food to easily carry.

It was an easy trip. And it indeed felt a lot like freedom.

My borrowed Brompton by the Rhône.Image: Quartz/Cassie Werber